İSTANBUL — Two weeks after protests erupted in Turkey, a mixed crowd of millennials and Gen-Zers gathered in Kadıköy, awaiting the arrival of Davide Martello, the legendary ‘Piano Man’ who played during the Gezi Park protests.

Martello had announced his return to İstanbul on social media, inviting locals to his live performance in Kadıköy’s Mehmet Ayvalıtaş Meydanı park on April 2.

However, before even a single note could be played, authorities – apparently having understood the symbolism of his planned event – detained both Martello and confiscated his piano immediately upon arrival at the park. Both Martello and his instrument were subsequently deported in a series of events that linked the present to the past, with reverberations for the future.

Turkey is currently witnessing its most significant social uprising since the Gezi protests rocked the country in 2013. Within hours of İstanbul Mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu’s arrest, citizens took to the streets and to social media platforms, making and sharing powerful imagery that instantly solidified the new movement’s spirit.

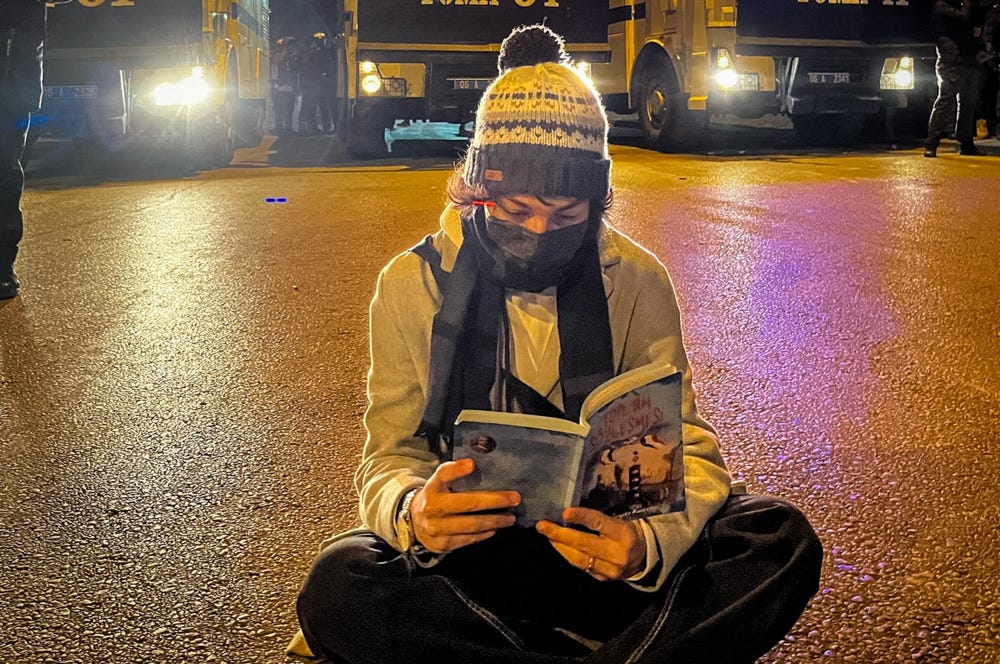

A gas mask-clad whirling dervish getting sprayed with tear gas by riot police. A young woman reading Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s ‘The Social Contract’ in front of water cannon trucks. These visual forms of protest, reminiscent of the creative spirit of the Gezi movement, reveal a resilient opposition attempting to challenge an increasingly authoritarian regime in a climate where expressing dissent has become incrementally more dangerous and constrained.

Işıl Eğrıkavuk, a Berlin-based artist and author of the book ‘Global Protests Through Art: collaboration, co-creation, interconnectedness’, said a decline in traditional democracy across the globe has shifted the way people protest, citing examples from Turkey, Hong Kong’s Umbrella Movement and the United States’ Occupy Wall Street.

“These movements have embraced artistic and performative expressions … to challenge authority and offer alternative ways of engaging with politics,” she told Turkey recap, describing moments of protest as “ruptures” or “instances that break away from societal norms and open up new spaces for imagination, dissent and dialogue.”

In other words, when traditional avenues of dissent are denied – when journalists face imprisonment, media outlets are shuttered or controlled by state-aligned actors and when citizens are arrested for voicing their discontent – communities turn to more artistic and symbolic forms of resistance to express their political grievances.

Creative resistance in Gezi

When students occupied Gezi Park in 2013, they not only hoped to save a green space from redevelopment, but also hoped to push back against the growing state clampdown on freedom of expression and civil liberties.

“At Gezi Park, what struck me most was the sheer inventiveness of the demonstrators,” Eğrıkavuk said. “In just a few days, the park became more than a protest site—it evolved into a vibrant communal space where people from diverse backgrounds came together to cook, eat, sing, dance and express themselves in ways that went beyond traditional activism.”

Symbols of creative resistance flowed across Turkey during the Gezi protests, manifesting in many forms: street art of gas mask-wearing penguins served to mock media censorship and iconic images of the “woman in red” being blasted by tear gas served to further mobilize protesters.

Such visual elements were accompanied by speakers across the country blaring Duman’s Eyvallah, and resistance rallying cries like ‘Her yer Taksim, Her yer dereniş’, meaning ‘Everywhere Taksim, Everywhere resistance.’

And, of course, there was performance art. One of the most striking examples was the “Standing man”, an act of non-violent political resistance by performance artist Erdem Gündüz. He stood for eight hours in the middle of Taksim Square, facing the Atatürk Cultural Center in protest of the escalating police violence during the Gezi protests.

This silent protest quickly went viral with #duranadam. Hundreds of others joined in solidarity across the country.

Davide Martello, the “Piano Man” of Taksim Square, was another unifying performance artist who, during the height of the protests, spontaneously diverted from a road trip, stopping in the square to play his piano.

Martello played for three consecutive nights to thousands of captivated protesters, including a 13-hour-long marathon. It was rumored that “even the police put down their batons” to watch the then-31-year-old play. The peaceful moment was shattered on the fourth night, when tear gas once again filled the square.

Lisel Hintz, an assist. prof. of international relations at Johns Hopkins University, said the various forms of art during the Gezi protests helped create a culture of shared collective experiences.

“These all work to let those frustrated by the government know they’re not alone, to heighten the public salience of grievances, and to build collective identity and shared emotions,” she told Turkey recap.

Such forms of protest grab attention, share information and evoke strong reactions, all playing a part in “how people become invested in protest [and] why they are willing to risk crackdown by showing up,” Hintz continued.

Student protesters from the Gezi demonstrations echoed this sentiment.

“I participated in Gezi because I thought we were actually going to change something in the country,” a 29-year-old visual artist from İstanbul told Turkey recap. “I was a university student at the time. We were drunk on hope.”

“I wasn’t political before. I never really thought about it. But Gezi opened my eyes. It changed how I see the world,” reflected a 30-year-old photographer, also a student protester of the Gezi movement. “I suppose we were a bit naive. We didn’t really know what we were doing back then. We got gassed. We made art. We thought we were changing the country.“

However, the optimism of the Gezi movement was quickly extinguished in the aftermath of the 2013 protests, as waves of arrests swept through activist networks while simultaneously imposing increasingly draconian restrictions on freedoms, throwing outspoken dissent into the closet for years to come.

According to Amnesty International, the Gezi protests saw 11 deaths, over 8,000 injuries and more than 3,000 arrests. Several individuals connected to the Gezi protests were rounded up, years after the movement – most notably the Gezi prisoners of conscience. Gezi Park activists, from artists to human rights lawyers, served jail time, were forced into exile or simply fled to avoid politicized trials.

Even the protest slogan ‘Everywhere Taskim, Everywhere resistance’ was banned from public space and media outlets. Protesters caught chanting it or waving posters were subject to harsh treatment and arrest.

The present movement

So, how does the resurgence of street protests in Turkey, emerging after years without massive demonstrations, resemble the creative resistance of Gezi?

Eğrıkavuk said she sees many similarities in the current political protests, “in terms of creative expression with local interpretations” in the form of performative dance and marriage proposals before police lines.

This includes protesters dressed up in costume – most notably the instantly iconic Pikachu running from police in Antalya. Comedy and satire have been pervasive in this current movement as well, mostly seen through protest signage and shared memes.

“Humor helps symbolically to erode the power of targeted government figures, bolster protesters’ sense of agency - i.e., you may have water cannons but we have wit,” said Hintz.

This increases the online visibility of protest messaging – “The more clever the meme or photographed poster (“you banned alcohol, we sobered up), the more widely it’s shared,” Hintz added.

The 29-year-old visual artist sees present-day protesters being inspired creatively by the Gezi movement, but noted: “The students today are also much more conscious than we were back then. They are more aware. I believe they perfectly understand [President] Erdoğan’s intentions and they plan and react in a very careful manner.”

Still, Eğrıkavuk was quick to highlight that “the current authoritarianism and police violence are much harsher compared to Gezi. The political atmosphere since then has become much more strict,” she said.

At the time of writing, thousands of protesters have been arrested and over 300 students are currently in jail.

Journalists have been beaten, arrested and deported. And a photographer who shot the now-iconic image of the gas-masked dervish was arrested at his home, in front of his children, before being released a few days later.

“I feel everything has gotten more dystopian over the years, but we have somehow learned to live with it,” said the visual artist. “I am an artist and every year, my career and the careers of other people in the industry are experiencing more and more setbacks, making it very hard to plan for the future.”

The mood in the country is a hazy mixture of apathy and hope. Students are showing up in contrast to their relative silence over the previous years. They hold signs reading, “Do not get used to hopelessness,” and "Hearts burning with hope bring victory through resistance.”

Meanwhile, rap song lyrics from ‘Susamam’ (I will not be silent) resound from car speakers nationwide and are echoed in social media posts of an MP, showing a collective perseverance for creative dissent.

Reflecting on the current situation, the 29-year-old visual artist said, “The difference between now and Gezi is that I no longer believe protest will make a difference - but I protest anyway - we have nothing to lose.”

**Editor’s note: The names of protesters have been omitted on their request and for their safety.

Turkey recap is an independent, reader-supported newsletter that helps people make sense of the fast-paced Turkey news cycle. Contact us: info@turkeyrecap.com.

Subscribe here on Substack (or on Patreon for a student discount). Paid subscribers get full access to our recaps, reports, members-only chat and news tracking tools.

Turkey recap is produced by our staff’s non-profit association, KMD. We are an affiliate of the Global Forum for Media Development and aim to create balanced news that strengthens local media by supporting journalists in Turkey.

Diego Cupolo, Editor-in-chief

Emily Rice Johnson, Deputy editor

Günsu Durak, Turkey recap Türkçe editor

Ceren Bayar, Parliament correspondent