More than drones: Teknofest and Selçuk Bayraktar promote techno-nationalism among Turkey’s youth

ADANA – Fighter jets fly low over Adana Airport, trailed by a deep rumble. Helin Dağ, 21, watches the sky to follow their movements. Her friend Işıl Barış, 16, films the air show with her phone.

“I’m enchanted,” says Dağ, who points to her arms. “It gives me goosebumps.”

They are impressed by the F-16s, but this is about more than just jets in the sky. This is about “vatan sevgisi”, or love for the homeland, Barış tells Turkey recap.

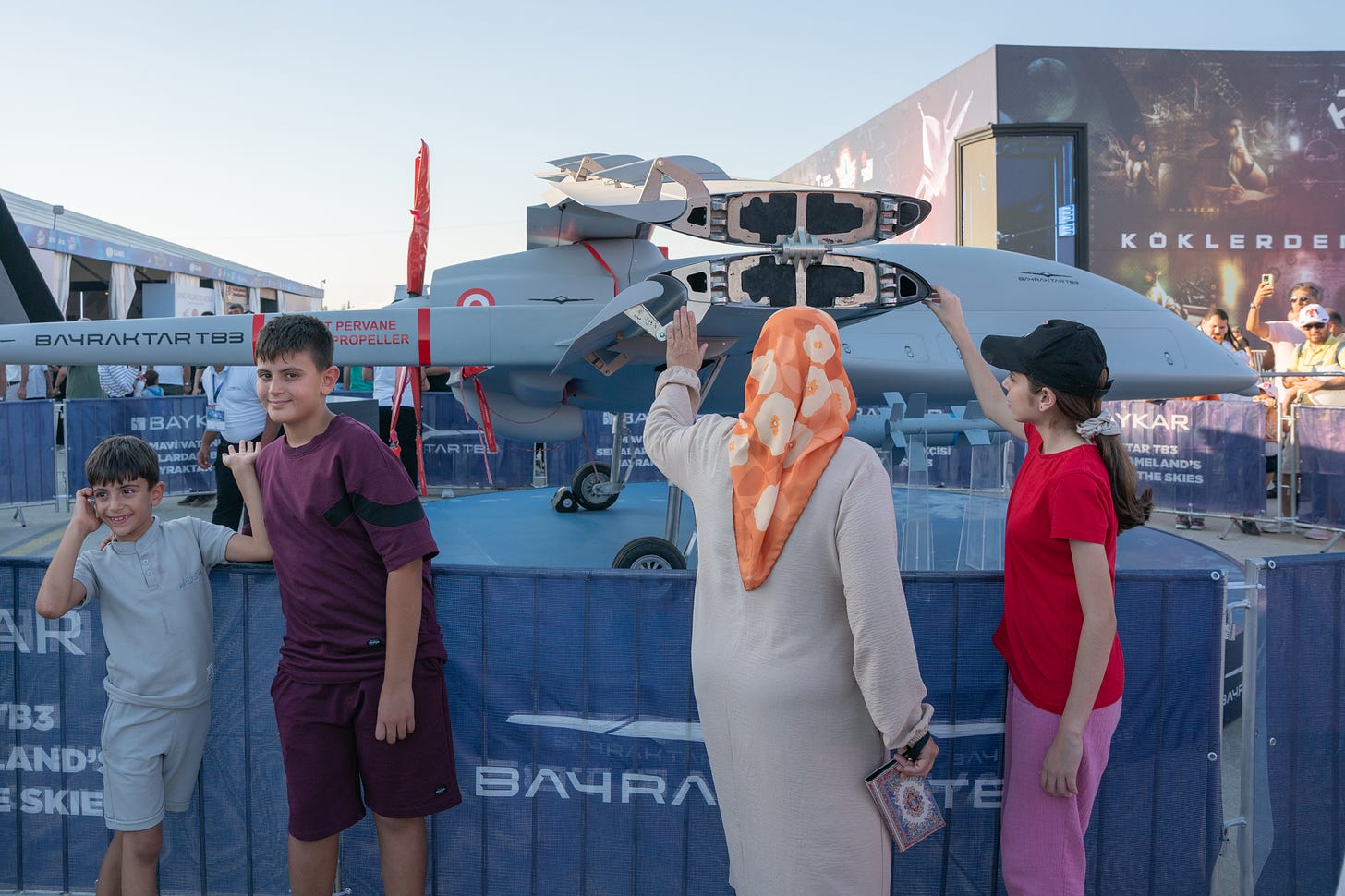

Such feelings of national pride are strong and widespread at Teknofest, a free, yearly event that showcases Turkey’s technology and defense industry to the public. People wait in line for a chance to touch Baykar’s Bayraktar drones or take selfies with the unmanned KIZILELMA fighter jet and other weapons on display.

Teknofest also hosts a large-scale student competition, in which more than a million youth take part in designing and developing technological solutions and projects.

Selçuk Bayraktar, the board chair for Baykar and the face of Teknofest, takes a central role in these events with aims to develop Turkish youths' interest in technology under the banner of the National Technology Initiative (Milli Teknoloji Hamlesi).

Both the drones and the technology competition boost nationalism within a narrative centered on increasing the self-sufficiency of Turkey’s defense industry. Students are encouraged to design and develop projects for the benefit of the country while a diverse audience at Teknofest repeats government talking points about the independence of Turkey’s drone production.

Taken together, the events also raise the profile of Selçuk Bayraktar, especially among the youth, at a time when the son-in-law of Pres. Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is considered to be among the possible successors to the president.

National Technology Initiative

In his speeches at Teknofest, Bayraktar, 45, presents himself as one of the 1.6 million young people who have registered for the Teknofest competition.

“We are the Teknofest generation,” he said during the opening speech in Adana. “Teknofest is not just a festival, it is also a youth movement that will change the future of our children and strives for a world that is safer, more peaceful and more prosperous.”

The festival, the competition and many other technological educational programs within the National Technology Initiative are organized under the banner of the T3 Foundation, where Selçuk Bayraktar is the chair of the Board of Directors.

“Our goal is to make children and students aware of the possibilities of science, education, technology, engineering, mathematics,” says Elvan Kuzucu Hıdır, chair of the Board of Trustees of T3 Foundation.

She explains they have programs for all ages and lists a range of projects in fields like AI, quantum technology and drones. She also highlights the goal is to develop more technology in Turkey, so the nation will no longer depend on others.

Teknofest is the public face of the program, but there is also a more strategic element to the National Technology Initiative.

“If you look at the situation in the world, it is important to develop your own national technology,” Hıdır told Turkey recap.

To reach this aim, T3 operates a dozen science centers in Turkey, in addition to one in Azerbaijan and one in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. New science center centers are planned for Montenegro and Kyrgyzstan.

Hıdır said the group aims to organize Teknofest in İstanbul and Cyprus next year, and indicated interest from Indonesia, as well as several African and Balkan countries.

“We want to move our projects abroad, especially to our close and brotherly countries,” Hıdır added.

Student competition

One of the participants in the Teknofest competition is Önder Ihsan Kul, 19, who together with his team designed an all-terrain robot that can assist in search and rescue operations.

“Think about soldiers for instance, when they get injured we can send our robot to rescue them,” Kul explains.

He mentions Selçuk Bayraktar as an inspiration, Kul calls him a ‘pioneer’.

“He is someone who is close to the Turkish youth. Not only students like us, but also children are fans of Selçuk abi,” Kul says. “I have met him, he is not a formal person to us, but someone who feels close.”

Kul’s groups received the second place prize in the Champions League category from the hands of Bayraktar, himself.

Kul, who studies electrical engineering at İstanbul Technical University, adheres to the ideals of the National Technology Initiative, which focuses on the citizens that are “placing their faith in their country’s strength and future.”

“Every researcher you see here produces technology in order to add a product to our country's technology inventory and to represent our country on the international stage,” Kul says about the initiative.

Techno-nationalism

All of these programs have a conservative and nationalist air to them, argues Diğdem Soyaltın-Colella, an assist. prof. at the University of Aberdeen. More specifically, Turkey’s drone program could be viewed within the context of techo-nationalism, she said.

“Techno-nationalism makes linkages between capacities of a country in producing high-tech, it can be weapons but also other development projects like bridges, tunnels … and how it is related with a country’s national security, economic prosperity and regime success,” she told Turkey recap.

“It is a tool especially at the hands of rising middle powers … governments are using technological sectors in different ways to promote national pride and to challenge global politics,” Soyaltın-Colella continued. “And this also is paying back in nationalism at home and can mobilize supporters because they see their government is challenging the global power game.”

“It is the butter on Erdoğan’s bread,” Soyaltın-Colella added.

In the same light, she said the National Technology Initiative should also be seen as a scientific, nationalist and conservative program that focuses on decreasing Turkey’s dependence on other countries. Yet a central problem in contemporary Turkey is that many highly-educated people, especially engineers, are often choosing to pursue careers abroad.

“So [the Erdoğan government] is giving this kind of scientific, rational, high-tech image on the one hand, but on the other hand, it's a very heavy, rigid, patronage bureaucracy,” Soyaltın-Colella said.

Elvan Kuzucu Hıdır, from the T3 Foundation, disagrees with suggestions that Teknofest promotes Justice and Development Party (AKP) policies.

“It is not true,” she said. “Millions of students apply to be part of this festival, we don’t ask their opinion or which party they support. Adana has a [Republican People's Party] CHP mayor and he was also part of the open ceremony of the festival.”

With the majority of opposition parties supporting Turkey’s drone program, discussions about the human rights implications of the weapons on display are often absent at the festivals, in mainstream politics and society, more broadly. Recent reports have detailed the use of Turkish drones against civilian targets in Syria and reportedly also Ethiopia.

“I'm really fascinated by how people became blind, or eye-washed by Teknofest, about this positive and victorious image of Turkish defense industry, but on the other hand of the story, there are civilians being killed [with] these drones,” Soyaltın-Colella said.

National security

The wish to increase the independence of the defense sector emerged long before the AKP existed. The imposition of US arms sanctions on Turkey following the 1974 invasion of Cyprus is considered to be the start of a long process that raised investments in domestic defense materials to reduce foreign supply chain dependencies.

Still, much of the current AKP discourse links the party to many of the nation’s technological improvements, including in the defense industry, argues defense expert Çağlar Kurç, an assist. prof. at Abdullah Gül University.

“Starting from 2013, the AKP started to talk more about how they invested in Turkish defense industries, how they were able to produce indigenous or local and national weapon systems. And from then on, we see the defense industry being incorporated into the AKP success story,” Kurç told Turkey recap.

He continued, saying the defense industry remains a high-priority sector, as many proponents can argue its development is a matter of national security.

“What that means is that you basically tell the public that we need to protect the defense industry, we need to invest more, because it’s linked to the survival of the state,” Kurç said.

The narrative also feeds into the idea Turkey is situated in an unstable region and faces constant threats from outside. Often stirring up this sentiment is Erdoğan, himself, who also at Teknofest suggested Israel might attack Turkey next.

“I need to state something very clearly here. In our region, an insidious plan is being put in practice that will not be limited to Gaza, the West Bank and Lebanon. You don’t need to be a prophet to see and understand where the ultimate target of this plan is,” he said in his speech.

Such existential threats resonate with the Teknofest attendees interviewed by Turkey recap, many of which expressed suspicion towards the United States and European nations.

“We feel proud,” says Gökmen Güçlü, who came from Aksaray to Adana to visit Teknofest with his wife and son. “It’s 100 percent Turkish, we are not dependent on the outside anymore.”

“Now you produce yourself, you can trust it,” he continues. “When you buy from abroad, you can't trust it. For example, what do they do with the things we buy in America? They watch you all the time.”

While Turkey’s defense sector has indeed grown, industry experts highlighted that Turkey is not currently fully self-sufficient and that absolute autonomy is practically unattainable. Kurç also noted Turkey remains a NATO member that imports arms and components mostly from the US and Europe.

“There's a difference between the discourse and the reality,” Kurç said. “The discourse might be: ‘We're not going to cooperate’ or ‘We're going to turn to BRICS’, but when it comes to the defense industry, Turkey is integrated into European and American supply chains,” he added.

This newsletter is supported by readers via Substack and Patreon. Paid subscribers get full access to our recaps, reports, members-only chat and news tracking tools. All proceeds go towards sustaining our journalism.

Turkey recap is produced by the Kolektif Medya Derneği (KMD), an İstanbul-based non-profit association founded by our editorial team to support and elevate news media and journalists in Turkey. Contact us: info@turkeyrecap.com

Diego Cupolo, Editor-in-chief @diegocupolo

Gonca Tokyol, Editor-at-large @goncatokyol

Ingrid Woudwijk, KMD president @deingrid

Emily Johnson, Deputy editor @emilyjohnson

Damla Uğantaş, Tr Türkçe editor @damlaugantas

Azra Ceylan, Economy reporter @azraceylani

Dénes Jäger, Editorial intern @denesjager