On Feb. 21, Somalia ratified a 10-year maritime security agreement with Turkey, enabling Ankara to act as a security provider in Somalia’s waters. The news came after Somaliland, an unrecognized state looking to secede from Somalia, agreed to lease a part of its coast to Ethiopia.

Turkey’s involvement in Somalia increased during Ankara’s “zero problems with neighbors” era, which was spearheaded by former Foreign Min. Ahmet Davutoğlu. Once a successful foreign policy, it stumbled in the aftermath of the 2011 Arab uprisings.

The resulting isolation in its immediate neighborhood prompted Ankara to use military muscle to assert itself as a global middle power.

Particularly in Somalia, Turkey increased military and humanitarian aid assistance, in turn raising tensions with the United Arab Emirates (UAE), another influential actor in the region that has since pursued a rapprochement with Ankara. Today, the latest Ankara-Mogadishu deal could revive regional tensions if Turkey and the UAE don’t coordinate their foreign policies.

The developments come amid broader instability linked to the Israel-Gaza war, which has seen attacks by Houthis in Yemen threaten shipping routes through the Red Sea. Between the shockwaves of violence, state and non-state actors are advancing their own interests to maximize gains and harden defense lines.

With its Ethiopia deal, Somaliland aims for international recognition as a separate state. For its part, Ethiopia seeks to regain direct water access after Eritrea broke away in 1991. Both are long-standing goals and not directly related to recent Houthi attacks.

Still, Turkey’s new mandate to defend Somalian sea borders could pave the way to a low-intensity naval conflict with Houthi rebels in the near future and further expand regional tensions. Such a scenario is not in Ankara’s interest and could be best avoided through coordination with the UAE.

Zero problems

The “zero problems” policy came as one of the lynchpins of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) after it was elected in 2002. It envisaged extending Turkey’s influence in its neighborhood and beyond through cooperation instead of competition.

In this vein, Turkey invested heavily in economic and development initiatives, as well as softer cultural diplomacy policies. Though after the general failure of the Arab popular uprisings, sitting regimes quickly froze their relations with Turkey and teamed up to counter its weight in the region.

The final nail in the “zero problems” coffin was the 2013 military coup in Egypt, which suppressed the Muslim Brotherhood. From then onwards, Turkey’s external politics became increasingly securitized and Ankara’s growing interest in Somalia came in the context of this series of events.

Ankara has since become a key international presence in Somalia despite initiating its projects when Mogadishu was isolated due to internal chaos and instability caused by the Al-Qaeda-linked Al-Shabab militant group.

Turkey-UAE competition

In August 2011, then-Turkish PM Recep Tayyip Erdoğan visited Somalia’s besieged capital. Soon after, Turkey launched a fast-growing humanitarian aid operation, which in time facilitated significant economic investments.

Notably, Turkish companies obtained the operating rights to Mogadishu’s port and its international airport. Expanding Turkish presence in the following years also drew threats from the jihadist group and, in response, Turkey initiated military support for Somalia, eventually opening a large military base there in 2017 to train officers in the Somali National Army.

Turkey’s military involvement has since fueled geopolitical tensions in the Horn of Africa and beyond. It particularly alarmed the UAE, which was also heavily invested in the region and was competing with Turkey for influence in Libya, the eastern Mediterranean and elsewhere.

The two countries diverged significantly on their relations with Somalia, including defense cooperation, development and humanitarian aid, control over economic assets and thorny questions regarding Somalia’s federal states, such as Somaliland.

The UAE was actively engaging with these states, while Turkey took a more cautious approach because of its proximity to Mogadishu, which does not want to see these entities empowered.

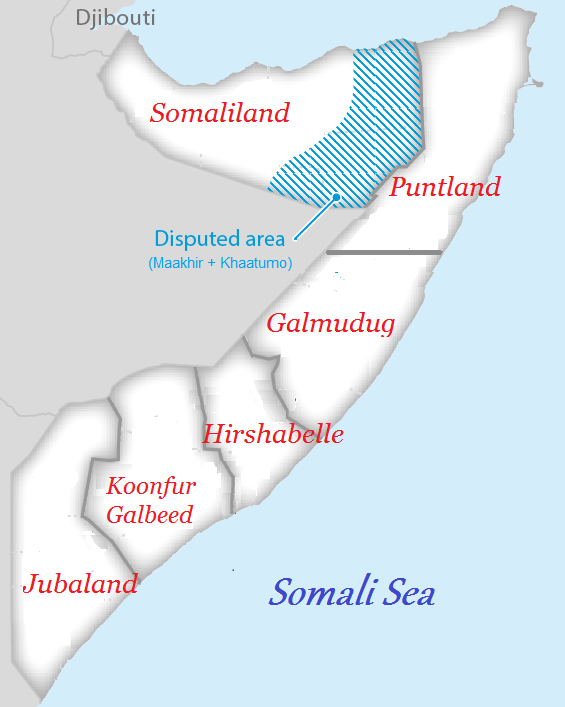

The Emirates increased its support to Somaliland and initially planned to open its own military base in the territory. It likewise stepped up military and economic support for Puntland, a quasi-autonomous region in eastern Somalia, where it had been funding the Maritime Police Force and, in 2017, obtained development rights to its main port.

Vice versa, Somalia’s federal member states were alarmed by Turkey’s increased partnership with Mogadishu after 2017. Somaliland has long-feared Mogadishu may reverse its de facto independence and this sentiment has grown after the lifting of a UN arms embargo on the federal government of Somalia on Dec. 1, 2023.

Throughout, Puntland and smaller states have pushed for Turkey to pursue a more evenly balanced aid and development program in its dealings with Somalia and the federal member states.

Regional thaw

Since 2022, a thaw in Turkey’s relations with the Emirates has helped reduce geopolitical and domestic tensions in Somalia. As recently as 2021, the two sides were sparring as part of a diplomatic crisis between Qatar and the gulf states. At the time, Turkey had backed its blockaded ally by increasing supply deliveries and Turkish Airlines flights.

But ties have improved dramatically since early 2021. Turkey and the UAE signed several economic cooperation agreements, and the Emirates purchased Turkish drones for its military. As a result, the Somali government elected in 2022 was able to take a more balanced approach in its relations with the UAE and Qatar, breaking from the immediate past.

Yet it is clear that Ethiopia and Somalia are taking bellicose action against each other, which once again increases the risk of conflict in the region.

On Jan. 1, 2024, Ethiopia and Somaliland announced they signed a memorandum of understanding, stating Ethiopia would open dialogue to recognize Somaliland, in exchange for the 50-year lease of a coastal strip of land near the Red Sea port of Berbera.

In response, Somalia this month ratified a treaty giving Turkey rights to protect its maritime territory in exchange for 30 percent of revenues from Somalia’s offshore areas, which host prime fishing waters as well as oil and natural gas resources.

The treaty gives Turkey a massive advantage in exerting influence over the Horn of Africa and the western Indian Ocean. It may also be read as a move to balance Ethiopia’s influence.

The Emirates, which is currently on good terms with all actors – Ethiopia, Somalia, Somaliland and Turkey – is now forced to make a hard choice.

Given the competitive nature of UAE relations with Turkey in Somalia, these steps could further exacerbate divisions in the country, especially if the UAE decides to support Ethiopia and Somaliland.

Still, if Turkey and the UAE could work closely in Somalia, they may eventually help the nation become a more resilient state. This, in turn, would enhance Mogadishu’s ability to counter Al-Shabab militants.

As the two most involved external actors, Turkey and the UAE should build on their recently improved relations to coordinate interests in Somalia and encourage dialogue between Mogadishu and the federal member states, rather than deepening divides.

This could help prevent further geopolitical tensions, and return a modicum of stability to the sub-region, where Yemeni Houthis threaten to upend global trade.

This newsletter is supported by readers via Substack and Patreon. Paid subscribers get full access to our recaps, reports, members-only Slack and more. We also have pun-tastic merch. All proceeds go towards sustaining our journalism.

Turkey recap is an independent news platform produced by the Kolektif Medya Derneği, an İstanbul-based non-profit association founded by our editorial team to support and elevate news media and journalists in Turkey.

Send pitches, queries and feedback to: info@turkeyrecap.com

Diego Cupolo, Editor-in-chief @diegocupolo

Gonca Tokyol, Editor-at-large @goncatokyol

Ingrid Woudwijk, Managing editor @deingrid

Verda Uyar, Digital growth manager @verdauyar

Sema Beşevli, Editorial intern @ssemab_

Onur Hasip, Editorial intern @onurhasip