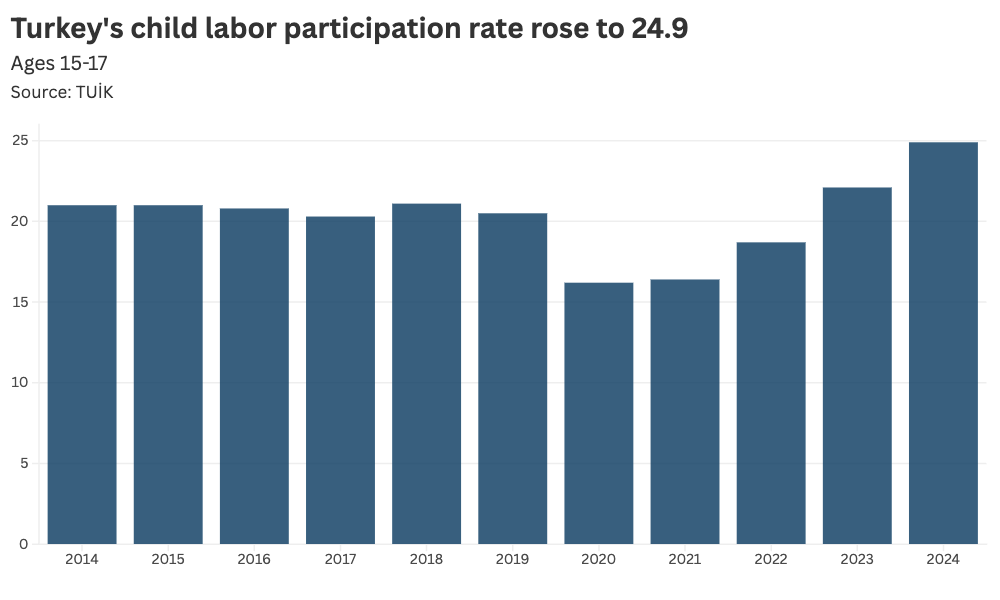

İSTANBUL — A growing number of children are working in Turkey. Labor force participation among 15-17 year-olds rose to 24.9 percent in 2024, up from 22.1 percent a year earlier, according to official data published Friday.

Youth employment has been trending upwards, surpassing pre-Covid rates in recent years as students and their families attempt to mitigate years of high inflation and the rising cost of living in Turkey.

At the same time, enrollment has been growing for the state-run Mesleki Eğitim Merkezi (MESEM), a vocational program that places high school students into the workforce for reduced salaries in return for on-the-job training.

More than 500,000 14-18 year-olds are currently enrolled in MESEM, up from 480,000 in the last academic year and 420,000 the year before that.

MESEM aims to prepare teens for employment. Its website states 88 percent of participants continue working in their training fields after graduating high school. Yet critics say the program legitimizes child labor under precarious conditions with inadequate oversight to protect students, some of which have lost their lives.

At least 10 MESEM participants died on the job last year. Recent examples include Arda, a 14-year-old who was crushed by a metal-bending machine, Erol, a 15-year-old who was trapped under chipboard panels, and Zekai, a 16-year-old who fell in a construction site.

“The MESEM system is nothing but the state-sponsored expansion of child labor,” said Taner Akpınar, a board member at the FİŞEK Institute Science & Action Foundation for Child Labor.

He added, “Small businesses operating outside the law have long sought to fill insecure and flexible work positions through child labor. Children are employed as workers under the name of ‘vocational training,’ but they have no social rights.”

What is MESEM?

Established in 2016, MESEM operates under the Ministry of Education and offers high school students, ages 14 and up, vocational training opportunities in 33 labor sectors.

According to program promotional materials, participants opt out of a five-day high school curriculum and, instead, work at least four days a week with one day reserved for regular school lessons.

In MESEM, 9th, 10th and 11th-grade students are paid 30 percent of the minimum wage, while 12th-grade students receive 50 percent of the minimum wage.

Additionally, students receive social security (SGK) and state-funded insurance for work accidents as well as occupational diseases. Upon completion, students obtain Kalfalık and Ustalık certificates, with the latter granting them legal rights to open their own businesses.

The state also covers a portion of the wages, incentivizing employers to participate in the program. Yet state inspections conducted at over 94,000 participating businesses found more than 8,400 enterprises did not meet occupational safety standards, exposing MESEM students to dangerous conditions on the job.

Bending the rules

Because each employer is different, work conditions can vary widely. In turn, the MESEM program on paper can contrast deeply with the program experienced by students.

MESEM participants have claimed they were paid in cash and worked without insurance. Some also said they were required to work on the one day per week that they were supposed to attend school. The same is true for their allotted day off per week.

As a result, some students work more than the program’s maximum allowed 30 hours per week. A recent FİSA report on the program found that student laborers can work up to 12 hours a day.

Ömer Faruk, a 15-year-old MESEM participant in İstanbul, said he often gets called on his day off.

“If we don’t go, the boss comes to our house. I work six days a week and earn 12,000 liras,” a salary of about $315 USD per month, he told Turkey recap.

Ömer is employed in the manufacturing sector and attends school one day per week. When asked why he enrolled in MESEM, he responded:

“My only dream is to open my own shop. I chose MESEM because I didn’t want to go to school. I thought I could work, earn money and learn a trade at the same time.”

He added, “What will I do by studying? I don’t dream of going to university. What happens to those who go to university? They are unemployed. At least I’ll have a job.”

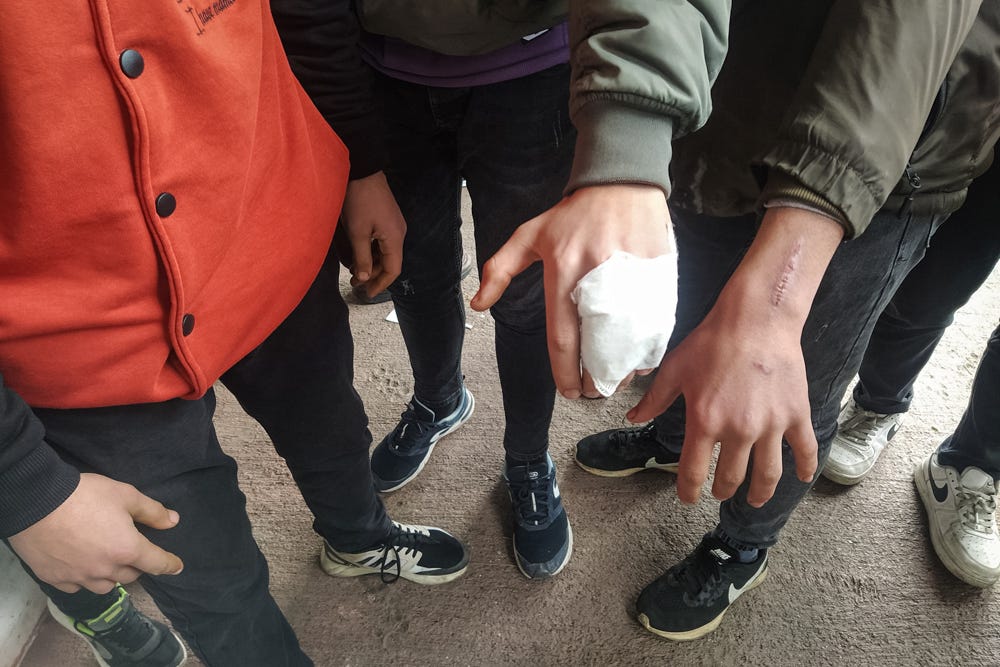

Ömer continued, describing a time he cut his hand while working. He said his boss accompanied him to the hospital, but avoided telling medical staff the injury was a workplace accident.

“He didn’t even mention that it happened at work. It was presented as a normal accident,” Ömer said.

As a result, Ömer did not get his medical treatment covered by state insurance, which would require him to file a “work accident report” from the hospital.

Ömer said he returned to the job after his hand healed, but dislikes the work culture, stating he is asked to do “all kinds of work” and is “constantly subjected to insults and humiliation.”

“It affects my psychology," he said, adding he began smoking cigarettes and drinking alcohol regularly to cope with the stress and fatigue.

Most MESEM employers declined requests for comment. One small business owner who participates in the program spoke briefly on condition of anonymity.

“These children are not studying. They are learning a trade thanks to us,” he told Turkey recap.

When asked if students should work full-time schedules like adults, he returned to work without answering.

Emek Gençliği, a youth labor organization, shared the following testimonial from a MESEM student quoted in a recent report:

“I am supposed to come to school and attend classes one day a week. But the boss doesn’t allow me to come. He says, ‘You won’t learn anything at school anyway. Come and work. You’ll learn more here than at school.’ When I told him that I was marked absent, he said, ‘Don’t worry about the absences. Just come to work. I’ll talk to the school and get your absences cleared.’”

The Ministry of Education did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this report.

‘You’ll earn money’

Opponents of MESEM often criticize the program for taking students out of school, exposing them to hazardous conditions and failing to apply protections through state supervision.

Akpınar, of the FİŞEK Institute, emphasized that the system aims not only to create vocational opportunities, but also to provide cheap labor.

“There is a MESEM unit in every vocational high school, and students are directed to these units in various ways,” Akpınar told Turkey recap. “Students who are unsuccessful in education or facing financial difficulties are directed with phrases like, ‘Switch to MESEM, you’ll earn money.’”

Akpınar said he believed MESEM was created because of steep declines in the number of students applying to a previous apprenticeship system in Turkey.

“Employers that had difficulty finding apprentices demanded the creation of the new structure,” he said.

“If children were truly provided with healthy conditions to learn a trade, no one would object to that. But the reality is not like that,” he added, noting the majority of students in MESEM come from low-income families and enroll out of financial necessity.

Limited intervention from unions

Labor unions also criticize MESEM, often stating it exacerbates child labor problems in Turkey rather than providing vocational training.

Nuran Güleç, an expert from the United Metalworkers’ Union (Birleşik Metal İŞ) which is affiliated with DİSK, said that following the death of MESEM student Arda, the union began conducting research to identify child labor in their members’ workplaces.

In many unionized factories, labor rights representatives requested employers take preventative measures against child labor, especially preventing the employment of teens under the age of 16. However, the representatives found some employers employed MESEM children under the pretext that “their school sent them.”

“During occupational health and safety inspections, we encountered child laborers in some factories. Thanks to being unionized, we were able to intervene in these situations more quickly,” Güleç told Turkey recap.

She added many teens under 16 have been observed in what her union would classify as “dangerous working conditions”. Güleç also noted their participation in MESEM is not always for financial reasons, and that understanding the driving factors requires more nuanced studies.

“Families and children may accept work at early ages due to a lack of trust in the current education system,” Güleç said.

Turkey recap is an independent, reader-supported newsletter that helps people make sense of the fast-paced Turkey news cycle. Contact us: info@turkeyrecap.com.

Subscribe here on Substack (or on Patreon for a student discount). Paid subscribers get full access to our recaps, reports, members-only chat and news tracking tools.

Turkey recap is produced by our staff’s non-profit association, KMD. We are an affiliate of the Global Forum for Media Development and aim to create balanced news that strengthens local media by supporting journalists in Turkey.

Diego Cupolo, Editor-in-chief

Emily Rice Johnson, Deputy editor

Günsu Durak, Turkey recap Türkçe editor

Ceren Bayar, Parliament correspondent